Before it became the ultimate forbidden fruit, the Praeputium Domini was one of the most holy relics in Christendom centuries before medieval legends of King Arthur’s search for the mythical Holy Grail gained popularity.

When Jesus appeared in a vision to Saint Catherine of Sienna in the year 1366, he took her hand in “mystical marriage”at a divine wedding attended by the Virgin Mary, John the Apostle, St. Paul, and St. Dominic. King David was there too, strumming those signature “secret chords” on his harp for the heavenly bridal party. Jesus sealed his spiritual marriage to Catherine with a holy wedding ring made from the foreskin of his penis. Visible only to Catherine, she wore her priapic wedding band until her death at age thirty-three.

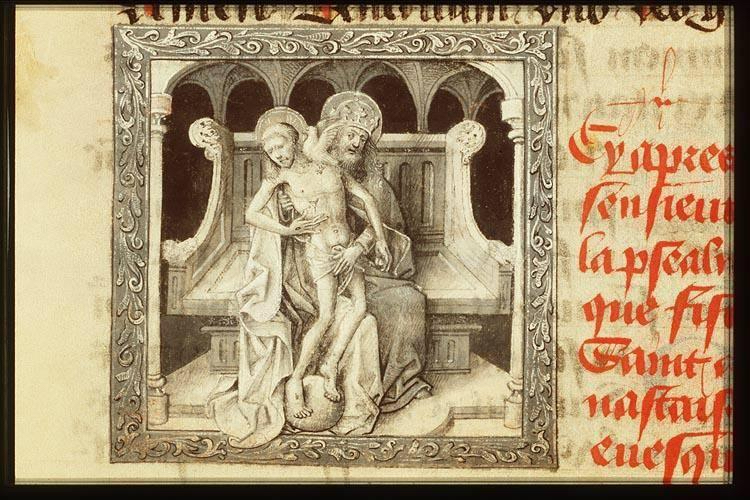

From the perspective of the early twenty-first century, the notion that a Doctor of the Church believed that she had an invisible piece of Jesus’s penis wrapped around her finger seems somewhat icky. While Christian artists—Catholics and Protestants like—have never shied from depicting Jesus as the sexy son of God, today’s Catholics spend less time meditating upon the most intimate part of the Body of Christ than their medieval and early modern forebearers. If you ever entertained such thoughts during Mass, they most likely triggered an attack of Catholic guilt rather than the divine elation many saints felt when their thoughts turned to the Praeputium Domini. Despite the Church’s reputation for prudishness, why did the foreskin of Christ loom so large in Catholic cosmology for much of its history? The fascinating history of the Praeputium Domini underscores that Catholicism has always been a bit queer.

Before it became the ultimate forbidden fruit, the Praeputium Domini was one of the most holy relics in Christendom centuries before medieval legends of King Arthur’s search for the mythical Holy Grail gained popularity. In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus was ritually circumcised eight days after his birth in accordance with Jewish law. According to various mystical revelations and local traditions, Mary preserved her son’s foreskin in a jar of oil and passed the relic on to John the Apostle. The foreskin purportedly came into the possession of Charlemagne around 800 CE. Magnanimously, Charlemagne donated the foreskin to Pope Leo III. Although St. Bridget of Sweden had a vision that confirmed the Vatican held authentic foreskin of Christ during the fourteenth century, historians have counted no less than twenty-one churches and abbeys claimed to possess the relic throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance eras. The sacred relic remained on prominent display at the Vatican, where it attracted pilgrims until the sack of Rome in 1527. Townsfolk from the Italian village of Calcata claimed to have recovered the foreskin from one of the purported looters by 1557. The small parish church remained a pilgrimage destination until thieves allegedly stole the foreskin and its jeweled reliquary in 1983.

As thousands of pilgrims sought healing and blessings from a mummified piece of the baby Jesus’s penis, others reported supernatural encounters with the divine foreskin. Indeed, St. Catherine of Sienna’s devotion was hardly an outlier in medieval and early modern devotional writings. During the thirteenth century, St. Agnes Blannbekin’s confessor reported that as the saint meditated upon the Holy Foreskin, “she felt with the greatest sweetness on her tongue a little piece of skin like the skin of an egg, which she swallowed. After she had swallowed it, she again felt the little skin on her tongue with sweetness as before, and again she swallowed it. And this happened about a hundred times.” A century later, St. Bridgit of Sweden not only had visions in which the Virgin Mary related a secret history of Christ’s childhood and the location of the “real” Praeputium Domini, but also tasted the holy foreskin. St. Bridgit was so overwhelmed by the “sweetness” of the “membrane” that upon swallowing it she felt “a sweet transformation in all her members and the muscles of her members.” Males also documented miraculous encounters with the foreskin of Christ, as several abbots and bishops claimed that their churches held the “authentic” Praeputium Domini because they witnessed it emit drops of blood during the Mass. Fascination with the Holy Prepuce hardly diminished by the scientific revolutions of the seventeenth century. As astronomers took their first close look at the planets through newly invented telescopes, the theologian Leo Allatius concluded that the foreskin actually ascended into Heaven with Jesus and became the rings of the planet Saturn.

Although claims that Vatican officials forbade discussion of the Praeputium Domini upon pain of excommunication have no basis in historical fact, its continued veneration had become a source of embarrassment for prelates. Protestant reformers cited the Holy Prepuce as the most egregious example of an “idolatrous” economy based on dubious relics, and most of the alleged foreskins perished in the tumult of the French Revolution. While modern historical scholarship confirms that these medieval relics certainly had questionable claims to authenticity, we must also remember that the intentions and devotions of those pilgrims who sought them were nevertheless genuine. By the nineteenth century, veneration of the Praeputium Domini diminished—but never fully ceased—as the Vatican took an increasingly hard line against sensual expressions of faith.

For queer Catholics at the dawn of the third millennium, the history of the Praeputium Domini represents more than a voyeuristic curiosity from a bygone era. The procession of saints, bishops, emperors, theologians, and pilgrims who sought tender yet tangible connections to Christ through contact with his foreskin shows that articulations of faith need not conform to the rigid heteronormativity that has dominated Catholic orthodoxy for the last century and a half. In recognizing Catherine of Sienna as a Doctor of the Church and elevating St. Bridget as a patron saint of Europe, Church leaders affirm that Catholicism has tolerated and even celebrated erotic encounters with Christ in ways that verge on prurient by that standards of the post-Vatican II era. Yet when we take an inclusive view of Church history, we see that contemporary LGBT+ identities are no more “intrinsically disordered” than beloved saints who described sensations comparable to an orgasm when swallowing the foreskin of Christ. Whether these saints received the highest grace or tasted the ultimate forbidden fruit, their expressions of faith merit the same respect, compassion, and sensitivity as queer Catholics in the twenty-first century.