The most Catholic country in Southeast Asia also hosts the largest Pride celebration in the region.

In the Philippines, the annual Manilla Metro Pride celebration continues to shatter attendance records in a country that prides itself on being among the most “gay-friendly” nations in Asia. Manila held its first Pride march on June 26, 1994 on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising. While the organizers of “Stonewall Manilla'' consciously drew inspiration from that first intersectional struggle against LGBT+ oppression, one of the most important distinctions in its Filipinx incarnation was the prominent leadership of LGBT+ faith leaders like Bishop Richard Mickley. While a recent United Nations study shows widespread acceptance of LGBT+ people and identities in the Philippines since that first Pride march, marriage equality and workplace protections remain ongoing human rights struggles in the ethnically diverse chain of islands.

Indeed, the Philippines have a rich queer history extending back before Euro-American colonialism, and comprise one of the most linguistically and culturally diverse places on Earth. More than 106 million people speaking 187 different languages inhabit approximately 2000 out of this archipelago nation’s 7,641 islands. Complex gender terminology in these Indigenous languages reflect cultures that conceptualize gender as fluid rather than a fixed binary. The Tagalog word babaylan predates colonialism, and describes an individual revered for their spiritual power. While the term has feminine connotations, it also applies to transgender or third-sex individuals in honorific terms. Indeed, ethnographies describe babaylan in marriages to cisgender men. Postcolonial theorist J. Neil C. Garcia has shown that Spanish colonizers attempted to suppress same-sex intimacy among the islands’ Indigenous populations during the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Despite evidence for variegated articulations of gender and sexuality within Indigenous societies, Spanish colonial officials perpetuated a Sinophobic myth that Chinese migrants had imported “sodomy” to the Phillipines prior to European contact. When the United States governed the Philippines as a colony during the first half of the twentieth century, Protestant missionaries promoted Americanized standards of heteronormative sexuality.

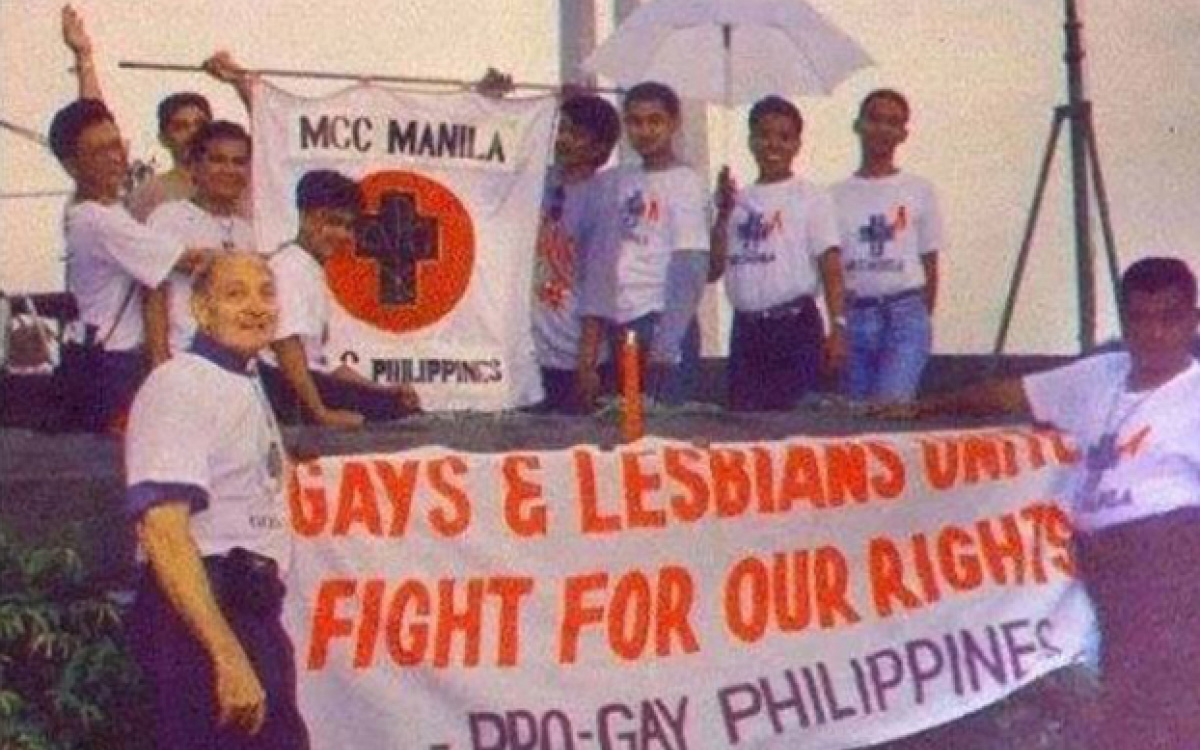

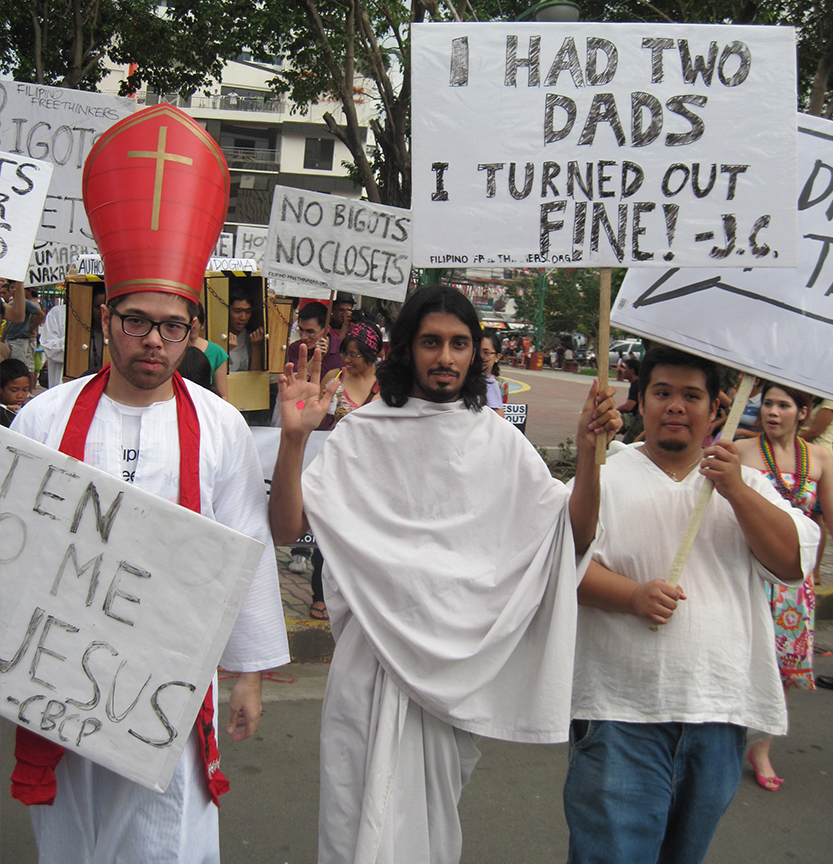

Beginning in the 1960s, thriving baklâ communities developed in urban centers as postcolonial successors to the babaylan tradition. Although pro-LGBT+ advocacy groups organized in the Philippines prior to the 1990s, they kept a low profile until the HIV/AIDS epidemic galvanized political action. On 26 June 1994, ProGay Philippines under the leadership of Oscar Atadero coordinated with Pastor Richard Mickley’s Metropolitan Community Church to organize the first Pride march in Asia. Fifty marchers paraded down the Quezon City Memorial Circle proudly proclaiming their queer identities. Pride demonstrations maintained an overt political posture through the early 2010s, gradually evolving into the vibrant community celebrations as the Millennial generation came of age.

Despite major generational and societal shifts toward a more inclusive society in the Philippines, the national government remains an obstacle to the expansion of LGBT+ human rights. The country’s Supreme Court made a final ruling against marriage equality in January 2020. Likewise, President Rodrigo Duterte claims that he “cured” himself of homosexuality, and often attacks political his opponents with homophobic invective. A survivor of child sexual abuse by a priest, Duterte has laced his philippics against the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines with accusations like “bishops are sons of bitches, damn you. It's true, most of them are gay.” Despite tensions between political leaders and the Catholic hierarchy on LGBT+ related issues, voters have proven more accepting. In 2016, Geraldine Roman became the first transgender woman elected to the Congress of the Philippines

The history of Pride in the Philippines shows how diverse peoples can forge national identity that is at once Catholic and queer affirming over the span of a generation. That work remains unfinished and ongoing, just like the revolution begun fifty-one years ago at the Stonewall Inn.