While gender nonconforming people faced certainly faced violence and discrimination during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, historians have also shown the idea of fixed gender binaries on the basis of biological sex assigned at birth emerged during eighteenth-century Age of Enlightenment. For most of the Church’s history, gender represented a fluid, contested, and evolving concept.

Although the term “transgender” emerged during the early 1970s, historians can map the experiences of individuals who did not identify with their sex assigned at birth or lived outside fixed gender binaries to the earliest writings of the Church. Despite recent claims by Vatican prelates that transgender lives and gender confirmation surgeries represent a novel twenty-first-century “Luciferian refusal to receive a sexual nature from God”—these assertions cannot withstand historical scrutiny of ancient and medieval Church texts. Indeed, the Church developed in a world where gender neither conformed to strict binaries nor was it immutable

Early Christian writings had a more complicated conceptualiztion of gender than biological sex assigned at birth. In the Judeo-Greco-Roman world, eunuchs comprised a recognized “third sex” that encompassed a spectrum of gender presentations and bodies. The term included intersex bodies, biological males who had nonsurgical alterations to their bodies, and males who had been both voluntariliy or involuntarily castrated.[1] Because Greek cultural misogyny regarded males as inherently closer to the divine ideal, holy women strove for apandro: “becoming male.”

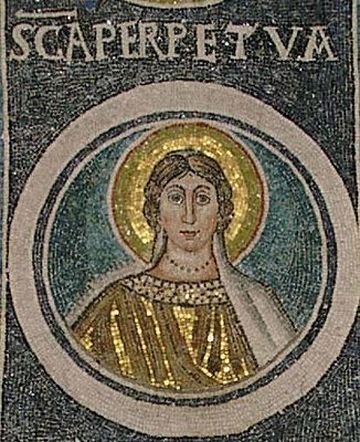

Christian texts reveal a complex interplay of biology, power, and culture influencing theologies of gender and salvation in the early Church. In St. Paul’s first-century letter to the Galatians, he declared there is neither “male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”[2] In the apocryphal second-century Gospel of Thomas, Jesus and Peter engage in a heated dialogue about Mary Magdalene’s sanctity. Peter exclaimed that “Let Mary leave us, because women are not worthy of life.” Jesus retorted, “Behold, I myself shall lead her so as to make her male, that she may become a living spirit like you males. For every woman who makes herself male will enter the Kingdom of Heaven.”[3] Likewise, the diary of St. Perpetua records her spiritual gender transformation before her martyrdom in gladiatorial combat during the third century, writing “my clothes were stripped off, and suddenly I was a man.”[4] The narrative culminates with a vision wherein her body transforms into that of male.

Scholarly debates about gender and salvation persisted into the Middle Ages. Medieval authors wrote approvingly of Christian women who donned men’s clothing to ascend to higher levels of spirituality, lived as males in monasteries, and occasionally married women.[5] Some theologians interpreted the first human in Genesis as an androgynous being, while others argued for a gendered binary. While gender nonconforming people certainly faced violence and discrimination during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, historians have also shown the idea of fixed gender binaries on the basis of biological sex assigned at birth emerged during eighteenth-century Age of Enlightenment.[6]

For most of the Church’s history, gender represented a fluid, contested, and evolving concept. Gender nonconformity within Catholicism represents an important yet overlooked tradition with deep roots in the origins of Christianity.

[1] Joan Roughgarden, "Transgender in Historical Europe and the Middle East," in Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 253.

[2] Galatians 3:28.

[3] Elizabeth Castelli, “‘I Will Make Mary Male:’ Pieties of the Body and Gender Transformation of Christian Women in Late Antiquity,” in Julia Epstein and Kristina Straub, eds, Body Guards: The Cultural Politics of Gender Ambiguity, (New York: Routledge, 1991), 30.

[4] “The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas,” in Herbert Musurillo, ed., The Acts of the Christian Martyrs (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1972).

[5] Karl Whittington, “Medieval,” Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1 May 2014, 1 (1-2): 125–129.

[6] Thomas W. Laqueur, Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 149.